Table of Contents

- President's corner

- ISHPSSB2025: A Brief Note from the Local Organisers

- Call for Proposals for the 2025 David Hull Prize

- Jane Maienschein: Sarton Medal

- In Memoriam: Michael Escott Ruse (1940–2024)

- Recent publications

- The Land Is Our Community: Aldo Leopold’s Environmental Ethic for the New Millennium by Roberta L. Millstein

- Lamarckism and the Emergence of ‘Scientific’ Social Sciences in Nineteenth-Century Britain and France by Snait B. Gissis

- Plasticity in the Life Sciences by Antonine Nicoglou

- Human socio-cultural evolution in light of evolutionary transitions by Yohay Carmel, Ayelet Shavit, Ehud Lamm & Eörs Szathmáry

- Charles Darwin: No Rebel, Great Revolutionary by Michael Ruse

- Credits

President's corner

In our multi-lettered, multi-disciplinary society, we often talk about “interdisciplinarity,” and the many ways in which we creatively bring disciplines and ourselves together. We also talk about inclusion and balance between all our disciplines, and how to widen our reach to others so as to add to the diversity and richness of the organization. In practice, what this usually means is making sure that there are always some “H's” (or historians), or “S's (or sociologists, or STS scholars), along with some “P's” (or philosophers), contributing to the program, serving on committees, or even serving as officers of the society. We work hard at that, and always have, and though we can always do better, we have met with some success given that our organization is flourishing with new scholars of diverse backgrounds and training joining us in increasing numbers. But we too rarely talk about the importance of including biologists, of many different kinds, or so it seems to me. I've always been aware of the importance of their participation in the organization, and indeed view it as foundational. It isn't only because we grew out of a need to discuss persistent problems in the biological sciences (in evolutionary biology to be exact), but because it is the one thing that we all have in common. Engagement with the “B” is in fact a unifying link, a kind of glue, that binds us together no matter how different we may be in our approaches, training, or disciplinary commitments. Without the “B,” we may have too little in common to function as a coherent society, and it is certainly what has kept me, and I know many others, excited about the organization.

With Jane Maienschein at AAAS Headquarters in Washington, DC.

With Jane Maienschein at AAAS Headquarters in Washington, DC.I was therefore happy that the need for doing more to include biologists —and biology— came up in a recent council meeting; and though I made a note of how many scientists participated in our last meeting in 2023, I nonetheless feel strongly that we need to do more. We need to make sure that biologists are on the meeting program, and that our program in turn offers them insights, and entices them to join us, and that their voices are heard in our governance. We also need to do more formally with scientific organizations too, affiliating with them formally, but also to attend meetings, organize sessions, and, if asked, serve as officers in organizations. For those of us with historical leanings, for example, we may help with establishing archives, performing oral histories, and curating important information. We also need to collaborate closely with more scientists, providing our best intellectual faculties, or in serving as ethicists or even critics, if needed. Serving the interests of the scientific enterprise need not involve mindless cheerleading or playing the distasteful role of “handmaiden” (gendered language deliberate here), I need note, but to act as independent scholars, constructive critics or even helpful policy makers. There are plenty of opportunities to do this. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (the AAAS), for example, has an entire section, Section “L,” dedicated to the History and Philosophy of Science, that organizes sessions and partakes in the annual meetings of the organization. Many of us have served as officers in that organization or have published in the journal Science, taking our insights into a staggeringly wide audience. If “engaged” scholarship is desirable, as many of us seem to think, then audiences as wide as AAAS, should definitely be considered.

With Jane Maienschein at the HSS Meetings in Merida, Mexico, following the awarding of the Sarton Medal.

With Jane Maienschein at the HSS Meetings in Merida, Mexico, following the awarding of the Sarton Medal.And there is much to gain in the way of real payback for these kinds of close interactions. We learn a great deal about science, and its organizations of course, but we also derive material support in the ways of grants, awards, and, even at times, employment. The National Science Foundation (NSF) of Washington, DC often provides us with travel subsidies to meetings, as just one example. And many of us have formed close partnerships with scientists and scientific organizations; past-president Jane Maienschein, for example, has been exemplary in that regard. A recent recipient of the prestigious Sarton Medal of HSS (see photos in this Newsletter and see figure below), Jane has led the way at Arizona State University and in places such as the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole working closely with scientists.

I am also happy to note that with Jane I currently serve on the Board of Directors, the body with oversight of the entire AAAS. We meet several times a year at AAAS headquarters in Washington, DC (see figure below).

It is a terrific opportunity to make scientists aware of the importance of our work, and how much it can actually inform science policies. At our board meetings, Jane and I often offer concrete historical examples to help guide discussion and decision-making or help clarify thorny issues on our agenda. I know that I have learned a great deal about the inner workings of a complex organization like AAAS, with an astonishing number of moving parts, but also its relations with government agencies, and its role in science diplomacy, an especially exciting aspect of the organization.

There is no good reason, not to be involved, and there are many such opportunities with other organizations. The ISHPSSB leadership has been actively seeking such partnerships, by for example endorsing cognate sessions with related societies, hosting off-year workshops on timely topics that bring together a multi-disciplinary set of scholars that include practicing scientists, and coordinating activities with groups such as International History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Group (IHPST), that is dedicated to science education. Indeed, one of the most promising directions we have taken is to bolster our involvement in science education overall. We have supported this trend in the organization for some time of course, and we especially look forward to the Porto meetings hosted by organizers keen on science education, but we have also opened channels of formal interactions with the IHPST through our own Education Committee currently co-chaired by Charbel-El Hani (Federal University of Bahia) and Ramsey Affifi (University of Edinburgh, UK). We look forward to many productive exchanges between ISHPSSB and IHPST that include a number of organized cognate sessions as early as our Porto meetings. We can do all this, and, I believe, continue to flourish even more, provided that we keep the “B” in a prominent location in ISHPSSB.

And, speaking of the Porto meetings, I am happy to report that all is going well, and that the website is up and running. I encourage everyone to start making plans especially about hotels given that they will likely fill up quickly given we are meeting in peak tourist season. Our program too is being sorted for a mid-April date, which is at about the same time we will have the special Newsletter with all the Porto details. In the meantime, please rely on the special meeting website elegantly designed by Maria Strecht Almeida.

Betty Smocovitis, President

ISHPSSB2025 – A Brief Note from the Local Organizers

Travel support

Applications for travel support for Porto 2025 is now open at the conference website here: https://ishpssb2025.icbas.up.pt/registration/travel-support/

Scholars who are independent, early career (within five years of having received the PhD), or still students are eligible to apply. The application deadline is 1 March 2025. Further details are available at the website.

Porto on the Douro River, by Derrick Brutel

Porto on the Douro River, by Derrick BrutelAccommodation

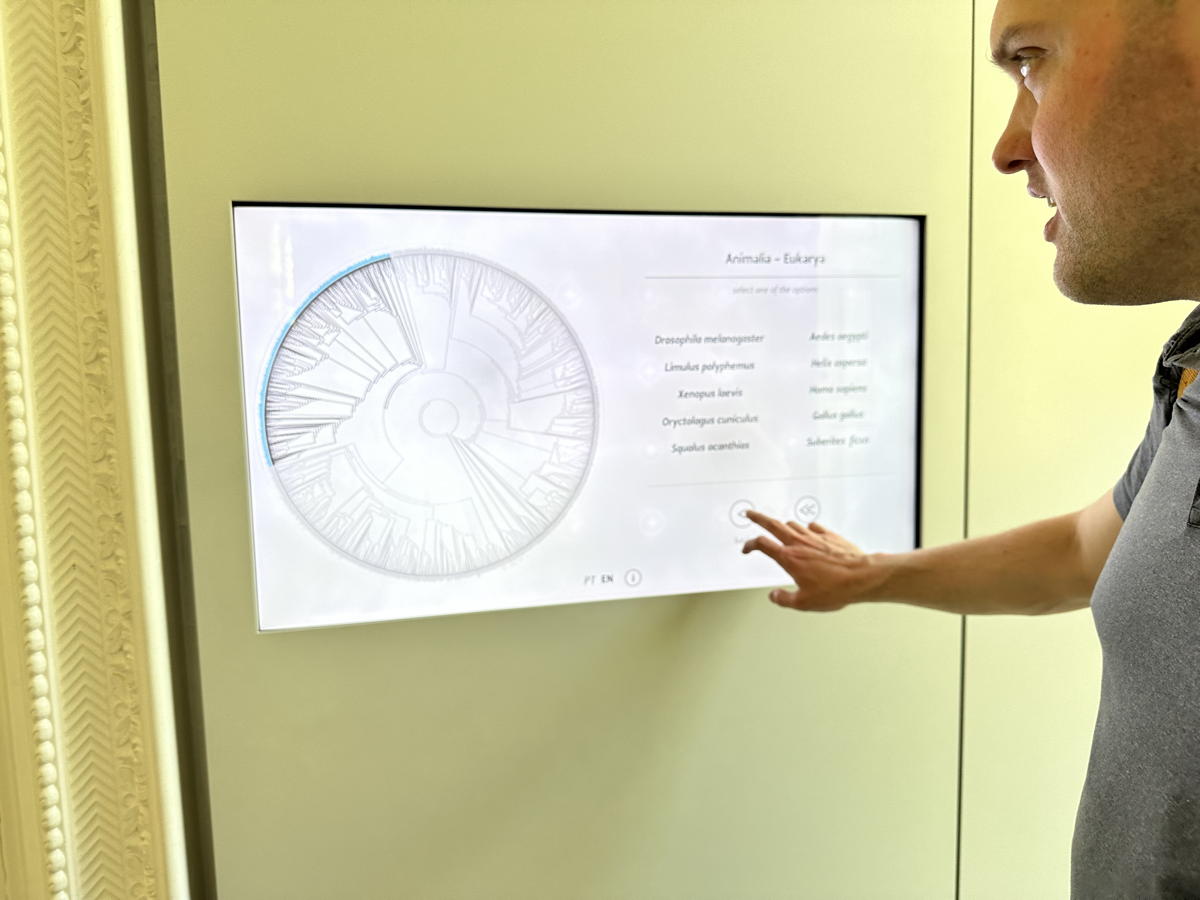

Exhibits in the Hall of Biodiversity, by Betty Smocovitis.

Exhibits in the Hall of Biodiversity, by Betty Smocovitis.All members planning to attend are encouraged to book their accommodations for the busy holiday season. A list of hotels is here: https://ishpssb2025.icbas.up.pt/planning/accommodation/

Porto presently receives many tourists during all seasons and it will be advisable to make hotel bookings in advance. Information on conveniently located hotels providing a specific code for conference participants is available at the conference website. Other accommodation options in the close vicinity of the venue exist and you are encouraged to explore these. Information about student university residencies will be made available as soon as possible.

Social program

As we approach the Porto 2025 meeting, we share some news on how things are evolving in the planning of the meeting and particularly the social/cultural program.

As usual, the social program will have the Conference Dinner as a main event. It will take place at the Hall of the Nations, at the Palácio da Bolsa; we are working towards an ISH-y and inclusive networking event. Other events are being planned for the social/cultural program: from events planned to take place on the opening day at the Hall of Biodiversity to an exhibition exploring the research conducted in the 1970s at the University of Porto around mesosomes and their description as artifacts of the technique. We must also mention that 2025 will be the year of the 50th anniversary of ICBAS (the logistic host of the ISHPSSB biennial meeting). We believe this will provide special opportunities for our conference. As part of that celebration, the exhibition 5225 – Stories of a ‘Molecular Disease' will be worth visiting for those who are interested in the history, philosophy and social studies of biology.

Exhibits in the Hall of Biodiversity. (Photos by Betty Smocovitis)

Looking forward to welcoming you to Porto.

Maria Strecht Almeida,

on behalf of the local organizers

Call for Proposals for the 2025 David Hull Prize

The David L. Hull Prize is a biennial prize established in 2011 by ISHPSSB to honor the life and legacy of David L. Hull (1935–2010). It is awarded to an individual who has made extraordinary contributions to scholarship and service in ways that promote interdisciplinary connections between history, philosophy, social studies, and biology and foster the careers of younger scholars. These are strengths that reflect the contributions of David Hull to our professions and to our Society.

Nominations for the Hull Prize are now open for consideration by the 2025 David Hull Prize Committee. The nomination packet should include the following materials:

- Nominator's name and email address,

- nominee's name and email address,

- a full CV of the nominee,

- citation text (maximum of 1000 words),

- and a minimum of two and a maximum of four letters of nomination, each signed by at least one member of ISHPSSB.

Those who submitted nominations in the recent past are encouraged to resubmit an updated nomination packet.

Nomination packets should be sent as PDF attachments to the chair of the 2025 David Hull Prize Committee, Prof. Gregory Radick (

Gregory Radick,

Chair of the David L. Hull Prize Committee

Jane Maienschein: Sarton Medal

Evelyn Hammonds, President of HSS with Jane Maienschein. In the background: Soraya de Chadarevian, President-Elect of HSS. Photo by J.P. Gutierrez, HSS.

Evelyn Hammonds, President of HSS with Jane Maienschein. In the background: Soraya de Chadarevian, President-Elect of HSS. Photo by J.P. Gutierrez, HSS.At the 100th anniversary meeting of the History of Science Society (HSS) in Merida, Mexico, Jane Maienschein was awarded the Sarton Medal, the most prestigious and highest honor bestowed by the organization, for a lifetime devoted to excellence in scholarship, teaching and service. Jane has been an effective and influential leader not only in HSS, where she served as past-president, but also in our own ISHPSSB, where she served as the first president, and recipient of the 2015 David L. Hull Prize. Her acceptance speech for the Sarton stressed the importance of interdisciplinarity and collaborations with scientists. Jane Maeinschein is currently University Professor, Regents Professor, and President's Professor at Arizona State University and serves as Director for the Center for Biology and Society.

Jane Maienschein being interviewed about her work by Nathan Crowe, Kate MacCord and Samantha Muka. Photo by Betty Smocovitis.

Jane Maienschein being interviewed about her work by Nathan Crowe, Kate MacCord and Samantha Muka. Photo by Betty Smocovitis. Jane Maienschein memorabilia. Photo by Matthew Tontonoz.

Jane Maienschein memorabilia. Photo by Matthew Tontonoz.In Memoriam: Michael Escott Ruse (June 21, 1940–November 1, 2024)

Michael Ruse (1940–2024).

Michael Ruse (1940–2024).Born in Birmingham, England, Michael Ruse completed his undergraduate degree in mathematics and philosophy at the University of Bristol, after which he completed a master’s degree at McMaster University in Canada. During the expansion of Ontario’s university system in the 1960s, he obtained a faculty position at the fledgling University of Guelph. During a year-long leave, he returned to the University of Bristol to complete a PhD. Although he had no formal training in biology, it was clear by the mid-1960s that biology was an important and mature science, especially in the wake of the discovery in 1953, of the structure of DNA and the subsequent rise of protein science and biochemistry more generally. After reading John Maynard Smith’s The Theory of Evolution (1958) and a few other biological treatments of evolution, he commenced writing his dissertation in the nascent field of philosophy of biology, placing him among the field’s founders. In my view, contemporary analytic philosophy of biology began with Morton Beckner’s, The Biological Way of Thought (1959), Thomas Goudge’s, The Ascent of Life (1961), Marjorie Grene’s somewhat less analytic, Approaches to a Philosophical Biology (1968), Michael Ruse’s, The Philosophy of Biology (1973), and David Hull’s, Philosophy of Biological Science (1974). In Philosophy of Biology, Michael laid the foundation for modern analytic philosophy of biology by providing a rigorous analysis and comprehensive treatment of nearly all the critical conceptual issues, including those that have remained contentious; it still stands as a tour de force—notwithstanding its thoroughgoing logical empiricist stance. He often remarked that it was during the writing of his dissertation that he discovered that he was a talented writer.

In 1962, Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions appeared. After the dust had settled, Michael considered it an exceptionally important contribution, in many ways, to our understanding of scientific change and advancement, but, for him, the central insight was that the history of science mattered to the philosophy of science. He set about understanding the history of evolution—particularly the Darwinian period. His first—still insightful and valuable—publication in this genre was “Darwin’s Debt to Philosophy” (1975). In 1979, his monograph, The Darwinian Revolution: Science Red in Tooth and Claw was published. It is not an accident that the title is the biological imitation of Thomas Kuhn’s 1957, The Copernican Revolution. The Darwinian Revolution remains an exemplar of the integration of philosophy of biology and history of biology. Over 70 books, covering a wide variety of topics—many translated in other languages—followed over the next 45 years.

His place as a founder of philosophy of biology does not rest on his publications alone. He founded in 1986 the first journal in the field, Biology and Philosophy (nurturing it into being one of the top four journals in philosophy of science). In 1995, he founded—and edited, from 1995 to 2011—the Cambridge Studies in Philosophy and Biology series, which published 80 of the most important books in the field. He was instrumental in the founding of the International Society for the History, Philosophy and Social Studies of Biology. He was a leader in championing evolution in the broader society and in promoting science education. A highlight of his public contribution to biological science was his testimony in the legal challenge to Arkansas’ 1981 “Balanced Treatment” Act, which required equal treatment in schools of creation-science and evolution-science. Although he was criticized by many colleagues for advocating a Popperian falsificationist demarcation criterion, he was clear that it was insufficient to demonstrate that creation-science was “bad” science. The constitution doesn't prohibit the teaching of “bad” science, it prohibits the teaching of religion as science.

He has received numerous prestigious research awards, including the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship and Isaak Walton Killam Fellowship. He was a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Canada (1986) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1986). The University of Bergen, McMaster University, the University of New Brunswick and University College London conferred on him honorary doctorates.

He was a complicated person. His work and personality courted controversy. As he has told so many of us over the last 50-plus years, “criticize me; just don’t ignore me.” He has certainly not been ignored and there is no shortage of criticism. He encouraged and supported women in their academic endeavours but could also make unwanted and gratuitous sexual—bordering on sexist—comments. He was generous of spirit and compassionate but could alienate those whom he—correctly or not—believed were squandering their talents. The influence of the parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14-30) remained with him all his life; the legacy of a Quaker upbringing. Although an atheist for most his adult life, he frequently said that when he died, he was convinced that he could say to a fictious God, “Master, you entrusted me with five talents. See, I have gained five more.”

He frequently commented on his love for, and gratitude to, his wife, Lizzie, (married Feb 16, 1985) and the joy that his five children and seven grandchildren brought him. He will be missed by them and the many others whose lives he enriched. His family, friends and the world have lost a Titan.

R. Paul Thompson PhD, FRSC

Professor Emeritus

Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, and Graduate Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

University of Toronto

Senior Fellow, Massey College (Toronto)

Recent publications

The Land Is Our Community: Aldo Leopold’s Environmental Ethic for the New Millennium by Roberta L. Millstein

A contemporary defense of conservationist Aldo Leopold’s vision for human interaction with the environment.

Informed by his experiences as a hunter, forester, wildlife manager, ecologist, conservationist, and professor, Aldo Leopold developed a view he called the land ethic. In a classic essay, published posthumously in A Sand County Almanac, Leopold advocated for an expansion of our ethical obligations beyond the purely human to include what he variously termed the “land community” or the “biotic community”—communities of interdependent humans, nonhuman animals, plants, soils, and waters, understood collectively. This philosophy has been extremely influential in environmental ethics as well as conservation biology and related fields.

Using an approach grounded in environmental ethics and the history and philosophy of science, Roberta L. Millstein reexamines Leopold’s land ethic in light of contemporary ecology. Despite the enormous influence of the land ethic, it has sometimes been dismissed as either empirically out of date or ethically flawed. Millstein argues that these dismissals are based on problematic readings of Leopold’s ideas. In this book, she provides new interpretations of the central concepts underlying the land ethic: interdependence, land community, and land health. She also offers a fresh take on of his argument for extending our ethics to include land communities as well as Leopold-inspired guidelines for how the land ethic can steer conservation and restoration policy.

Published with University of Chicago Press—30% discount with code UCPNEW: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/L/bo219284936.html Or free open access download: https://bibliopen.org/9780226834474

Roberta Millstein

Lamarckism and the Emergence of ‘Scientific’ Social Sciences in Nineteenth-Century Britain and France by Snait B. Gissis

This book has just been published in the Springer series: History, Philosophy, and Theory of the Life Sciences 2024.

You can also read a first review in: History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences (2024) 46:36 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-024-00640-8

Snait B. Gissis

Plasticity in the Life Sciences by Antonine Nicoglou

The University of Chicago Press recently released Plasticity in the Life Sciences by Antonine Nicoglou.

Plasticity has become an important topic in biology, with some even wondering if it has now acquired the theoretical importance in biology that the concept of the gene enjoyed at the beginning of the last century. In this historical and epistemological study, philosopher Antonine Nicoglou shows how the recurrence of the general idea of plasticity—throughout the history of the life sciences—indicates its essential role in the way we think about life processes. Although plasticity has become a key element in new evolutionary thinking, she argues, its role in contemporary biology is also not insignificant. Rather, as mobilized in contemporary biology, plasticity most often seeks to account for the specific nature of living systems.

The book is divided into two parts. The first takes up the history of plasticity from Aristotle to contemporary biology; the second part offers an original way of distinguishing between different phenomena described by “plasticity.” In the process, the author explores what has led some biologists to speak of plasticity as a way of overcoming genetic determinism.

Anne Strother

Human socio-cultural evolution in light of evolutionary transitions by Yohay Carmel, Ayelet Shavit, Ehud Lamm & Eörs Szathmáry

A widely read special issue from Royal Society Publishing Philosophical Transactions B is now free to access: Human socio-cultural evolution in light of evolutionary transitions compiled and edited by Yohay Carmel, Ayelet Shavit, Ehud Lamm and Eörs Szathmáry. The articles can be freely accessed directly at https://www.bit.ly/PTB1872

A print version is also available at the special price of £40.00 per issue from

Felicity Davie

Charles Darwin: No Rebel, Great Revolutionary by Michael Ruse

Michael Ruse's last book —what he said was going to be his final book— was published just a few days before he died on 1 November 2024.

You can find it at https://www.cambridge.org/9781009438940

Joe Cain

Credits

This newsletter was edited by David Suárez Pascal employing GNU Emacs and Scribus (both open source and freely available). I thank Betty Smocovitis for proofreading it and to all the ISH members who kindly contributed to this issue with their texts.

The logo of the society was generously contributed by Andrew Yang.

Submissions for the newsletter should be addressed at: